In the Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) released for the year 2020, which rated the perceived levels of public sector corruption in 180 countries around the world, most of the African countries, especially those in Sub-Saharan Africa, were included in the “Highly corrupt” category.

The top-ranked countries on the CPI were mainly from Europe, North America and Australasia. And some of these included Denmark, New Zealand, Finland, Singapore, Sweden and Switzerland.

While I appreciate the results of Transparency International’s CPI, I have always had reservations about its relevance and this is particularly because of offshore financing. It is true that many of those top-ranked countries have strong institutions and traditions built to promote transparency, but through various offshore schemes, they have continued to accept dirty money worth billions from poorer countries.

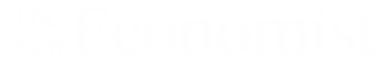

This money is being hidden by their banks and companies. In fact, some estimates indicate that African countries are losing at least US$88 billion in assets, which is illegally funnelled abroad using offshore financial structures. So, you may then wonder why Britain and the United States are ranked 11th and 25th when they are the same countries where the biggest chunks of this stolen money end up.

Much of the stolen funds are held in countries normally designed as “tax havens”. Estimates provided by Gabriel Zucman, the French Economist known for his research on tax havens, indicate that in 2014, 8 per cent ($7.6 trillion) of all the world’s financial wealth was held in tax haven countries of Switzerland, Singapore, Hong Kong, Jersey, The Bahamas and Luxembourg.

These figures do not include all the non-financial assets that are owned offshore, such as yachts, real estate, and art works, which he thinks may add up to another $2 trillion.

In his elegantly written book, Moneyland, Oliver Bullough notes that different nations are affected by offshore financing in different ways. Wealthy citizens of the rich countries of North America and Europe own the largest total amounts of cash offshore, but it is a relatively small proportion of their national wealth (about 4 per cent for the United States and 10 per cent for Western Europe), thanks to the large size of their economies.

But in Africa (taken as a whole), for instance, it is an astonishing 30 per cent while in Gulf countries, the total is 57 per cent. This is partly because in developing or un-democratic countries, it is easier for greedy unscrupulous officials to hide their wealth.

Thanks to the magic of the modern financial system and the anonymity provided by offshore jurisdictions that accept funds whatever provenance, money stolen by corrupt government officials and politicians in poor countries easily finds its way into western cities, such as Miami, New York, Los Angeles, London, Monaco and Geneva.

Think of Nigeria’s former president General Sani Abacha who is suspected to have stolen and stashed over $5 billion in foreign bank accounts. Almost three-quarters of the banks failed to adequately check whether the money in the accounts had been legitimately acquired; half of them failed to identify adverse information about their client and a third of them dismissed serious allegations made against their client.

These practices, which are highly complex and deeply entrenched, have flourished over the past decades with devastating impact, but have barely made it into the news headlines. And they have given rise to millions of disguised corporations, shell companies and bank accounts through which money is swiftly siphoned.

The money lost may have been spent on development of essential infrastructure, such as schools, hospitals and roads, and tackling hunger, but all these remain underfunded. And it is not surprising, for instance, that Africa’s richest woman is the daughter of Angola’s longest-serving president yet the rest of her nation struggles in what is essentially termed as a failed state.

Sadly, for the citizens, once ownership of the stolen public assets is obscured behind multiple corporate vehicles, and hidden in multiple jurisdictions, they are almost impossible to discover. Even when the corrupt regime from which the insider profited collapses, as it did in Zimbabwe, it is difficult – if not impossible – to find his/her money, confiscate it and return it to the nation it was stolen from.

Whereas wealthy people in societies across the West have also tried to keep money out of the hands of their governments and have developed clever tools, too, with which to do so, the amounts of cash invested offshore is a substantially small proportion if compared to their counterparts in poorer nations who actually operate under very skewed economies.

I agree that, unlike conventional countries, money has no physical borders – or border guards for that matter – and it’s difficult to implement sanctions against it. But if we want to put a stop to the escalating corruption levels, we must confront the corrupt individuals, amend the current rules on corporate transparency and find ways of dismantling the offshore structures that make it easy for them to hide public money from democratic oversight.

Mr. Mukalazi is the Country Director of

Every Child Ministries Uganda.

bmukalazi@ecmafrica.org